Sunshine: Facing the Unknowable, Accepting the Inevitable

1. Background

Radiation

It is no wonder that ancient

civilizations often deified the Sun.

It is the source of all life on

Earth. Without it, we would be a frozen husk of a rocky planet, no different

from any of the countless celestial objects in the night sky.

At the same time, it contains

some of the most dramatic forces in the universe. It’s gravitational force is

so large that it undergoes nuclear fusion, turning it from a bundle of gases

into a fiery plasma, with incredibly high temperatures and dramatic magnetic

fields – noticed here on earth in solar flare blackouts and auroras (the

Northern Lights).

It is so bright, even millions of

miles away, that we cannot stand looking into it for more than a fraction of a

second, lest we cause permanent damage to our eyes.

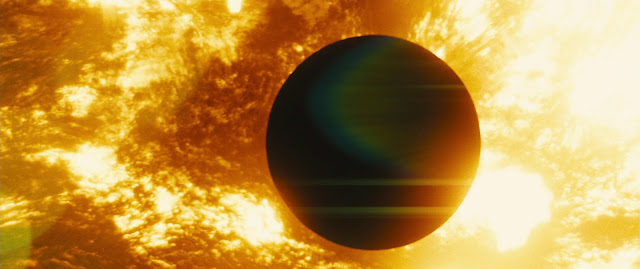

Sunshine (2007) is, on its

surface, another space movie. It predates other fantastic movies like The Martian and Interstellar, yet it fits right alongside them, and, in many cases,

surpasses them.

To take Sunshine at face value, however, is to massively undersell it.

I am a lifelong agnostic atheist,

a physicist, a non-believer in any sort of supernatural phenomenon, and also

someone who considers spirituality central to my life. In light of all this, I

have no reservations labeling Sunshine as a movie about the intersection between

spirituality and science, and how these are not only not mutually exclusive,

but necessary partners.

The premise of Sunshine is simple. The year is 2057.

Our Sun has suddenly started dimming billions of years early, plunging the

Earth into an endless winter, slowing killing off all life. One ship, aptly

named Icarus-I, was sent to restart the Sun several years previous,

mysteriously failing.

Aside from this, the viewer need

not know too much of the details of how life on Earth has evolved. The crew of

Icarus-II – as well as us, the viewers – have but one goal: deliver a massive

nuclear bomb to the Sun and set off a chain reaction that will jump-start the

Sun’s fusion.

We are introduced to a diverse

and competent crew. There is Cassie (Rose Bryne), the pilot; Kaneda (Hiroyuki

Sanada), the captain; Harvey (Troy Garity), comms officer; Searle (Cliff

Curtis), psych officer; Trey (Benedict Wong), the navigator; Mace (Chris

Evans), the engineer; and the main character, Capa (Cillian Murphy), the

physicist. Each of these characters plays an important role in this voyage, and

each of them equally comes to face their own very specific downfall.

2.The Harsh

Light of Day

The very beginning of the movie,

however, serves as a microcosm of the rest of the film.

We are shown Searle observing the

Sun on the observation deck, through a filtered window covering an entire wall.

With the Sun at a point where Searle has to squint in order to see it, he is

told by the computer that he is seeing 2% of the full brightness. Inquiring

over whether he could see 4%, he is told that that would, to paraphrase, burn

out his eyes. The best the computer can do is “3.1% for a period of not longer

than 30 seconds.” At this brightness, Searle is overcome by the light, getting

lost within it.

We are incapable of handling the

massive power of the sun, even over 30 million miles out. We can only truly

comprehend and experience a tiny, tiny fraction of that. Any more and we are

destroyed.

The next character we see

sunbathing in this way is Kaneda, the captain.

Each character’s death, too, is

foreshadowed at some point earlier in the movie. Searle, later in the movie,

with no way back to Icarus-II, turns off the filters in the observation room

and views the Sun at 100%. Kaneda, with no way back to the airlock in time,

faces the Sun rushing toward him on the heat shields, with Searle yelling

through the comms, What do you see?!

For Searle – and frankly, all of

the characters in their own ways – the titular sunshine becomes an obsession.

Capa and Cassie are haunted by dreams of falling into the sun. Searle and

Kaneda use the observation deck. And, as we see later, Pinbacker is consumed by

it.

There are many reviews that go

over the first two thirds of Sunshine, usually heaping praise, and following

that up with “…but, the last third of the movie turns into a slasher film, and

severely disappoints.”

The reason I chose Sunshine as my

third movie was because of this fact.

The first two thirds of the movie

set up our characters and the conflict well. We have Trey’s failure, leading to

Icarus II taking damage from the solar wind; we have Capa and Mace’s fight over

communication difficulties. We have dramatic visuals and reminders that any

error when dealing with something as domineering and overwhelming as the Sun

means near-certain death.

But, rather than dragging the

rest of the movie down, the last third presents the essence of the film. It is

where the big ideas that were set down in the first part are realized.

So, in analyzing and discussing

the last third of the movie, there’s one character we’re going to have to go

over: Pinbacker.

Pinbacker, as we learn at the

outset of the film, is the Captain of Icarus-I. He seems well-adjusted, and

there is little indication for what happened to Icarus-I, especially once we

find out it is still orbiting the Sun and transmitting.

We soon figure out that Pinbacker

has become a god-like entity whose skin is practically entirely burnt off – at

least, from what little we can see of him.

You see, the Pinbacker we deal

with in the last third of the movie is never directly seen. The effect that the

cinematographer decided to go with whenever Pinbacker is on screen is

practically identical to the effect that we get every time a character looks at

the Sun at near its full intensity. There is a high-pitched screech. A shimmer

of light. And much like the Sun, neither the characters nor the viewers are

able to stare directly at Pinbacker.

Pinbacker’s constant attestations

that he “spoke to god for 7 years” and that this is all part of the plans of a

higher power are no coincidence either.

Pinbacker is, yes, a real

character in the movie.

But he is not meant to literally be

a severely burned captain who somehow gained powers from staring at the Sun for

seven years.

Pinbacker is the personification

of madness. He is the Sun made manifest in human form. His tearing apart the

team, person by person, in the way each character feared most is intentional. It is these members

succumbing to the strain, fear, panic, and awe of being in the presence of

something so enormous, so strong, and so, frankly, holy. Believer or not, the

power of the Sun is enough to make you lose your breath. The first time I

learned that the sun was more than 99% of

the total mass of the solar system, I felt minuscule. I felt what I assume

is the same feeling one would feel in the presence of their own gods. It was a

spiritual experience.

And this sense of enormity, of

coming to terms with these huge, existential truths, is as likely to bring you

to grand revelations as it is to destroy you.

Staring into the Sun renders one

man an insane, otherworldly husk of a human being. It begins to pull in Searle,

hence his increasingly desperate attempts to figure out what Kaneda sees in his

last moments. It torments at least two of the characters with dreams of their

mortality.

The only character who makes it

out of the entire movie with any sense of peace is the very character who not

only has come to terms with what he must do (and what that means for him specifically),

but also the character who seems to have an intrinsic respect for the Sun as a

thing, not needing to parse its nature from any particular angle. He’s the ship’s

physicist, sure, which means that he understands the sun at its most

fundamental, yet he also has the most poetic view of the mission as a whole.

Asked by Cassie if he fears death, he describes the explosion as a rebirth, not

a fiery cataclysm. He is only able to face and deal with the enormity of the

knowledge imparted by the Sun because of his ability to face it, as well as his

sense of mortality, and let that pass through him.

It is because of all this that I

disagree with the consensus that Sunshine

is a missed opportunity of a movie, a perfect two-thirds of a movie with a

horrendous ending. Nothing could be further from the truth. The last third of

the movie contextualizes the beginning of the film. It takes a great sci-fi

movie and transforms it into a movie about our limitations as human beings, of

coming to terms with our own impermanence and of accepting that there is so

much that we, both individually and as a whole, will and can never understand.

3. The Dying of the Light

I have had a keen knowledge of

this fact from when I was very young, as I’ve mentioned in previous essays. I

first gained a comprehension of death around the age of 8 – a sense of

mortality that expressed itself in a strong dread, of trying to figure out how

long I had left with the things that mattered most to a child. I remember one

particular night where I was gripped by a fear of rabies after reading a story

from Scary Stories to Read in the Dark

and couldn’t sleep a wink, for fear that either myself or someone I loved would

be struck down by it. As I’ve grown, this dread has ebbed and flowed, but it

is, of course, part of the human condition. It is a struggle we all face at

some point or another. Attempting to wrap your head around it is asking to be

destroyed by it. It is staring into the void, allowing yourself to be taken in

by it. It leads to you running yourself in circles, trying to find another solution

to this discontinuation of your consciousness. Frankly, most of the time, I

think people just don’t think about it, avoid it by all costs, and deal with it

as a “well, that’s far enough away that we don’t have to worry about it.”

I don’t have an answer as to how

we as humans deal with this in a consistent and healthy way. If anyone does have the answer, please please please let me know. But it

is unavoidable. It is all-encompassing. It is awe- and terror-inspiring. And

ultimately, it is fundamental to all life.

I’m not sure that Boyle meant for

this film to be an allegory of existential dread, and of the limitations of

knowledge.

All I can say is that staring

into Sunshine has revealed, through

my lens, a tale that is both the story of a group of people trying to save the

planet through a “stellar bomb,” the story of space and isolation weighing on

us as humans, and a story of the crossroads where spirituality and dread meet.

I have a sense of spirituality

regarding the universe and this life, despite my lack of religious beliefs,

because it is an amazing and terrifying place. The same pathways that to some

say religion still fire within my brain, my heart, my body. Maybe they say

something different, but that is not an assessment on the veracity of whether

my worldview is right, or yours is, or anyone’s is. It is saying that

spirituality, in any of its forms, is a key part of being human. It is a drive

in us, and wherever that drive pushes us is more important than what is driving us, or why. Why care about the nature of matter

at its most basic levels or the universe on its largest scales if we’re being

purely scientific and practical? In my particular case, I find myself driven by

a need to understand as much as I can – a need that is driven into me both by

trying to pull apart everything and see its core, and by time nipping at my

ankles, reminding me constantly of how temporary my station on this earth is.

Yes, our endings are preordained

(unless, as I hope, San Junipero

becomes a reality!). But trying to wrap our heads around that and make it

simple, whether that be through a scientific lens, or a religious one, or a

psychological one, or a philosophical one, etc., is to miss the whole. All that

we can truly know is that sense of awe, that sense of smallness, and that sense

of having a purpose nonetheless.

Without drive, without amazement

in the face of this universe, what do we have?

5/5

5/5

Comments

Post a Comment